Every building material faces invisible forces deep within the Earth, and understanding tension stress—the pulling-apart force that fractures rock—reveals why certain natural stones outlast others by centuries. When tectonic plates drift apart or rock masses bend upward, tensile forces create weakness planes that geologists can identify and architects must account for. This geological reality directly impacts your project’s longevity: stones formed under high compression, like granite and dense marble, resist tension better than sedimentary varieties that developed in low-stress environments.

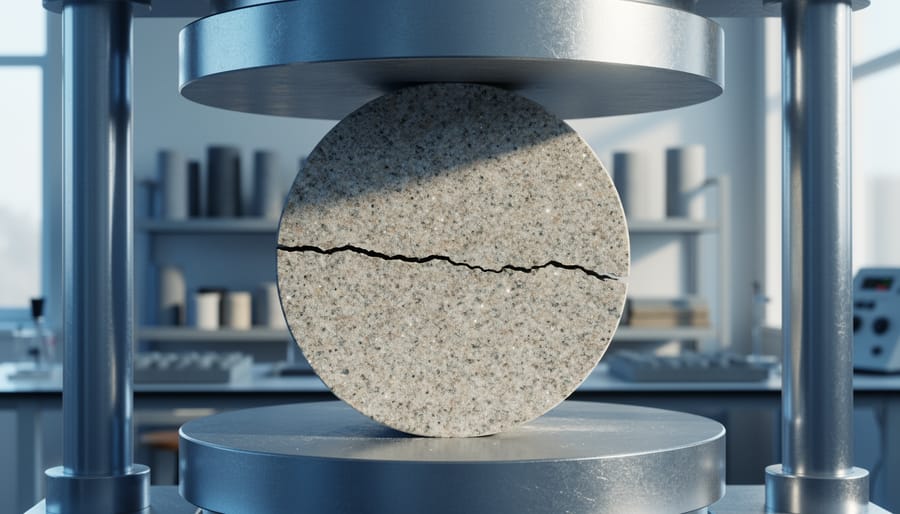

The difference between a cracked façade and stress-free installations lies in matching stone properties to applied loads. Natural stone that survived millions of years of geological tension carries inherent structural memory—crystalline bonds aligned to resist specific force directions. Modern testing quantifies this through Brazilian disc tests and four-point bending analyses, translating ancient geological processes into present-day load ratings.

This scientific foundation connects directly to your selection criteria. When you specify stone for vertical cladding, countertop spans, or structural elements, you’re essentially asking: will this material resist the same pulling forces that shaped its formation? Understanding tension stress geology transforms stone selection from aesthetic choice into performance-driven decision-making, ensuring your projects honor both geological heritage and engineering requirements.

What Tension Stress Actually Means in Geology

How Tension Stress Shapes Stone Formation

Tension stress plays a fundamental role in creating the durable characteristics we value in natural stone. When tectonic forces pull the Earth’s crust apart, they subject rock formations to tensional forces that influence their internal structure at a molecular level. This geological process, occurring over millions of years under specific temperature and pressure conditions, determines how stone will perform in architectural applications.

During formation, tension stress creates microscopic fracture patterns and grain orientations that actually enhance a stone’s structural integrity. As minerals crystallize under these conditions, they develop interlocking patterns that distribute forces efficiently. This natural arrangement makes materials like granite and quartzite exceptionally resistant to cracking and weathering. The slow cooling and pressure release during formation allows mineral bonds to strengthen, producing dense, stable material.

Understanding these formation mechanics helps explain why certain stone types excel in high-stress applications. Stones formed under significant tension stress typically exhibit uniform density and predictable behavior under load. The internal structure developed during geological formation creates natural pathways that dissipate stress rather than concentrate it, preventing failure points that could compromise integrity.

For professionals specifying natural stone, this geological background provides insight into material selection. Stones shaped by tension stress during their formation period demonstrate superior performance in exterior cladding, flooring, and structural elements where durability matters most. The same forces that shaped these materials millions of years ago contribute directly to their reliability in contemporary construction, making them proven choices for demanding architectural projects.

The Three Types of Geological Stress

Earth’s crust experiences three fundamental types of geological stress that shape our planet’s landscapes and test the resilience of materials, including natural stone. Compression stress occurs when forces push rock masses together, like tectonic plates colliding to form mountain ranges. This squeezing action can strengthen certain stone formations by increasing their density. Tension stress, our primary focus, happens when forces pull rock apart, creating zones of stretching that can lead to fracturing if the material lacks sufficient tensile strength. Finally, shear stress develops when forces slide past each other in opposite directions, similar to the movement along fault lines during earthquakes.

Natural stone’s remarkable durability stems from its ability to withstand all three stress types simultaneously. Formed over millions of years under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, materials like granite, marble, and limestone develop crystalline structures that distribute stress effectively. This inherent geological resilience translates directly to practical performance in architectural applications, where stone must endure environmental forces, structural loads, and thermal expansion. Understanding these stress mechanisms helps professionals select appropriate stone varieties for specific projects and anticipate how materials will perform over decades of service.

Why Stone That Survived Millions of Years Won’t Fail in Your Home

Comparing Geological vs. Structural Stress

To truly appreciate natural stone’s structural capabilities, consider the forces it has already survived over millions of years. Tectonic stresses that fold mountain ranges generate pressures exceeding 100 megapascals (MPa), equivalent to roughly 14,500 pounds per square inch. Marble formed under metamorphic conditions routinely withstands compressive forces of 1,000 to 3,000 MPa during its creation deep within the Earth’s crust.

By comparison, typical building applications subject stone to remarkably modest stresses. A granite countertop supporting kitchen appliances experiences loads of approximately 0.5 to 2 MPa. Even heavily trafficked commercial flooring rarely sees compressive stresses above 5 MPa. Tensile stresses in properly installed stone cladding systems typically range from 0.1 to 1 MPa, orders of magnitude below what the material endured during formation.

Consider limestone from quarries in Indiana, which formed under burial depths of several kilometers, experiencing overburden pressures of 50 to 80 MPa. When installed as building facades, these same stones face wind loads generating stresses of just 0.05 to 0.2 MPa. The disparity is substantial.

This geological perspective explains why properly selected and installed natural stone performs so reliably in architectural applications. The material arrives at construction sites pre-tested by nature under far more extreme conditions than any building will impose. Understanding this fundamental strength differential helps architects and designers specify stone with confidence, knowing they’re working with a material that has already proven its durability under incomparably greater forces.

How Different Stone Types Handle Tension

Natural stone’s response to tension stress directly reflects its geological origins. Each stone type develops unique characteristics during formation that determine its tensile strength and vulnerability to cracking under pulling forces.

Granite, an igneous rock formed from slowly cooled magma deep underground, exhibits excellent tension resistance. Its interlocking crystalline structure creates a tight bond between quartz, feldspar, and mica minerals. This dense composition typically withstands tension forces between 7-25 MPa, making granite ideal for applications like countertop overhangs and exterior cladding where cantilevers create tensile loads. However, even granite contains natural micro-fractures from its cooling history that can propagate under excessive tension.

Marble forms when limestone undergoes metamorphic recrystallization under intense heat and pressure. This process creates larger, interlocking calcite crystals that provide moderate tension resistance, typically 10-15 MPa. While stronger than its limestone predecessor, marble’s crystalline structure remains vulnerable to tension perpendicular to its natural bedding planes. Architects must consider grain direction when specifying marble for installations involving tensile stress.

Limestone, a sedimentary rock composed of compacted organic and mineral sediments, demonstrates the lowest tension resistance among common building stones, usually 2-8 MPa. Its layered formation creates natural weak planes where tension easily initiates failure. Dense limestone varieties perform better, but this stone generally requires substantial support in tension-prone applications.

Slate’s metamorphic origin gives it a distinctive foliated structure with strong cleavage planes. While slate resists tension well along its grain, it splits readily perpendicular to these planes. This directional weakness requires careful orientation during installation, particularly for flooring or roofing applications where flexural stress creates localized tension. Understanding these formation-based characteristics ensures proper stone selection and installation techniques that work with, rather than against, each material’s natural properties.

The Hidden Stress Points in Building Design (And How Stone Addresses Them)

Thermal Expansion: Where Synthetic Materials Crack

Temperature fluctuations pose significant challenges for building materials, causing expansion during heating and contraction during cooling. These dimensional changes create tension stress that can lead to cracking, warping, and structural failure in many synthetic materials. Natural stone, however, demonstrates remarkable dimensional stability thanks to its geological formation process.

Over millions of years, stone forms under sustained pressure and temperature deep within the Earth’s crust. This prolonged formation process creates an incredibly dense, interlocking crystalline structure where minerals are tightly bonded at the molecular level. Unlike manufactured materials that solidify rapidly, natural stone’s slow cooling allows its mineral components to settle into stable configurations with minimal internal stress.

This geological heritage translates directly into practical performance. Natural stone exhibits extremely low coefficients of thermal expansion, typically ranging from 4 to 12 micrometers per meter per degree Celsius. Compare this to concrete, which expands at roughly twice that rate, or plastics, which can expand ten times more. When temperature swings occur in building facades, flooring, or countertops, stone remains dimensionally consistent while synthetic alternatives struggle.

The dense structure also means heat moves slowly through stone, reducing rapid temperature differentials that cause material stress. Granite and marble installations frequently span decades without cracking from thermal cycling, even in environments with extreme seasonal temperature variations. This inherent stability makes natural stone particularly valuable for exterior applications, heated flooring systems, and spaces with high thermal loads where synthetic materials would require expansion joints or risk failure.

Load Distribution in Stone Flooring and Countertops

Natural stone’s exceptional performance in flooring and countertops stems directly from its geological origins. During formation, immense pressure creates a dense, interlocking crystalline structure that inherently distributes loads across a broader surface area rather than concentrating stress at single points.

When you place a heavy appliance on a granite countertop or walk across a marble floor, the stone’s molecular arrangement works to dissipate that force. The tightly bonded mineral crystals transfer weight laterally through the material, effectively spreading the load and minimizing localized stress concentrations that could lead to failure. This natural load distribution mechanism explains why stone surfaces can support substantial weight without cracking or deforming.

Density plays a crucial role in this performance. Granite typically ranges from 2.65 to 2.75 grams per cubic centimeter, while marble falls between 2.5 and 2.7. This density, combined with minimal porosity in quality stone, creates a rigid matrix that resists deflection under load. Unlike synthetic materials that may flex or compress, properly installed stone maintains its structural integrity.

The stone’s thickness further enhances load distribution. Standard 3-centimeter countertops provide superior resistance to point loads compared to thinner alternatives. For high-traffic flooring applications, designers often specify thicker slabs or reinforce installation with appropriate substrate systems to maximize the stone’s natural load-bearing advantages.

Understanding these geological properties helps professionals specify appropriate stone types and thicknesses for specific applications, ensuring long-term durability and performance while minimizing maintenance concerns.

Real-World Evidence: Ancient Stone Structures Still Standing

Throughout history, stone structures have withstood the test of time precisely because builders understood, intuitively or otherwise, how to work with stone’s natural stress characteristics. These enduring monuments provide compelling evidence of natural stone’s remarkable ability to resist tension stress when properly designed and installed.

The Roman aqueducts, some dating back over 2,000 years, remain functional today. The Pont du Gard in southern France exemplifies this longevity. Constructed without mortar, its massive limestone blocks rely on compression forces while arch designs minimize tension stress. Engineers distributed weight strategically across multiple tiers, demonstrating an ancient understanding of how stone performs best under compression rather than tension. The structure’s survival through countless earthquakes, floods, and weathering events proves stone’s durability when forces are properly managed.

Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame de Paris and Chartres Cathedral showcase even more sophisticated stress management. Flying buttresses redirect lateral thrust forces from vaulted ceilings, converting potentially damaging tension into manageable compression within thick stone walls. These architectural innovations allowed medieval builders to construct soaring spaces while protecting limestone and sandstone from tensile failure. The fact that these ancient stones endure centuries of wind loads, temperature fluctuations, and structural settling demonstrates exceptional stress resistance.

Ancient Greek temples like the Parthenon reveal similar principles. Massive marble columns transfer vertical loads efficiently while horizontal elements spanning between supports were sized to minimize bending stress. The Greeks selected specific marble varieties for their density and crystalline structure, properties that enhanced stress resistance.

These structures share common success factors: careful stone selection based on grain patterns and inherent strength, strategic load distribution through arches and columns, and architectural designs that minimize tension while maximizing compression. Modern architects and designers can apply these time-tested principles, combining ancient wisdom with contemporary engineering analysis to create natural stone installations that perform reliably for generations.

Selecting Stone for Stress-Critical Applications

High-Traffic Flooring Considerations

When selecting flooring for high-traffic commercial spaces, building lobbies, or residential entryways, understanding a stone’s geological stress history becomes crucial for long-term performance. Stones that formed under significant compressive stress typically exhibit superior durability under constant weight loads and foot traffic.

Granite stands out as an exceptional choice for high-traffic areas due to its formation under intense heat and pressure deep within the Earth’s crust. This geological process creates interlocking crystal structures that resist wear, scratching, and cracking. Similarly, metamorphic stones like quartzite and slate, which underwent transformation under tremendous stress, demonstrate remarkable resilience in demanding environments.

Limestone and marble, while beautiful, formed under different geological conditions and may show wear patterns more quickly in high-traffic zones. These stones work better in moderate-traffic areas or when treated with appropriate sealants and finishes.

For maximum performance, specify stones with tight grain structures and minimal natural fracturing. Request information about the quarry depth and geological formation from suppliers, as stones extracted from deeper deposits typically experienced greater compressive forces, resulting in denser, more durable material that withstands heavy use without compromising aesthetic appeal.

Exterior Façades and Cladding

Exterior façades and cladding systems demand careful stone selection because these applications face the harshest environmental conditions. Wind loads create both compression and tension forces across stone panels, while daily and seasonal temperature cycling causes expansion and contraction that can stress mounting systems and the stone itself. Stone that has undergone significant geological tension stress during formation typically exhibits superior flexibility and fracture resistance, making it better suited for exterior exposure.

When selecting stone for façades, professionals should prioritize materials with proven track records in similar climates. Granite varieties that formed under high-pressure metamorphic conditions generally perform well due to their tight crystalline structure and resistance to moisture infiltration. Certain sandstones and limestones can also excel when properly oriented, with bedding planes positioned to distribute wind loads effectively rather than concentrate stress along vulnerable planes.

Temperature cycling presents particular challenges in regions with freeze-thaw conditions. Stone with low porosity and high tension strength resists the expansion forces created when moisture freezes within the material. Understanding a stone’s geological history helps predict its performance: materials formed in tension-rich environments often possess the internal structure needed to withstand repeated thermal stress cycles without developing microfractures that compromise long-term durability and aesthetic appeal.

Countertops and Horizontal Surfaces

Countertops and horizontal surfaces represent one of the most tension-sensitive applications for natural stone. When stone extends beyond its supporting base as a cantilever or overhang, the underside experiences significant tension stress. Understanding how different stones respond to these forces is essential for safe, functional installations.

Granite typically handles cantilevers exceptionally well due to its interlocking crystalline structure and high tensile strength. Industry standards generally allow granite overhangs up to 12 inches without additional support, though thickness and specific mineral composition affect this capacity. Marble, with its softer calcite-based structure, requires more conservative support—typically limiting unsupported overhangs to 6-8 inches. Quartzite performs similarly to granite when properly oriented, while slate’s layered structure makes it particularly vulnerable to tension stress in cantilevered applications.

Support requirements vary dramatically by material. Kitchen islands with seating areas demand careful engineering, as the combined loads from the stone weight and occupant stress concentrate at mounting points. Fabricators often install steel brackets, corbels, or knee walls to transfer tension forces into compression. For materials with lower tension resistance, reducing overhang dimensions or adding visible supports becomes necessary. Proper substrate attachment and edge reinforcement prevent catastrophic failure where tension stress naturally concentrates at the weakest cross-sectional points.

Installation Techniques That Honor Stone’s Natural Stress Resistance

Proper installation transforms natural stone’s inherent geological strength into lasting architectural performance. By respecting how stone responds to tension and compression forces at the molecular level, installers can prevent premature failure and maximize longevity.

Begin with adequate support systems that distribute loads evenly. Stone naturally resists compression far better than tension, so every installation should minimize tensile forces. For countertops, support brackets should be spaced no more than 24 inches apart, with additional reinforcement at joints and overhangs. Cantilevers require steel brackets or corbels that transfer tensile loads away from the stone itself, preventing the microscopic crack propagation that leads to fracture.

Joint placement deserves careful consideration. Rather than fighting stone’s tendency to develop natural stress planes, strategic joints accommodate movement while maintaining structural integrity. Control joints should align with high-stress areas like corners, direction changes, and large format transitions. These planned weak points prevent random cracking by providing predetermined paths for stress relief. Leave joints slightly flexible rather than rigid—elastomeric sealants allow thermal expansion and contraction without transferring tension into the stone.

Movement accommodation is essential for large-scale installations. Natural stone expands and contracts with temperature fluctuations, and restricting this movement creates destructive tensile forces. Install expansion joints every 12 to 20 feet in flooring applications, depending on climate conditions and stone type. For facades, incorporate flexible anchoring systems that permit slight movement while maintaining alignment. Pin connections work better than rigid bolts, allowing stone panels to shift minimally without creating stress concentrations.

Back-buttering tiles and ensuring full mortar coverage prevents hollow spots where tensile stress can concentrate. Inadequate adhesive contact creates unsupported areas vulnerable to flexural tension from foot traffic or thermal cycling. Modern thin-set mortars offer excellent flexibility, absorbing minor movements that would otherwise stress the stone.

Professional installers who understand these geological principles don’t just follow specifications—they think dimensionally about force distribution, creating installations where human engineering complements millions of years of natural formation.

Understanding tension stress geology transforms how we evaluate and select natural stone for construction and design applications. When you recognize that millions of years of geological forces have already tested a stone’s structural integrity, you gain confidence that extends far beyond surface aesthetics. The cracks that didn’t form, the layers that remained intact, and the minerals that bonded under extreme conditions all serve as nature’s quality control process.

For consumers and professionals alike, this geological perspective provides a scientific framework for decision-making. Rather than relying solely on appearance or marketing claims, you can assess stone based on its proven track record of withstanding real-world stresses. A granite countertop that survived tectonic compression or a marble façade quarried from tension-resistant formations carries inherent performance guarantees that manufactured materials simply cannot replicate.

The stone’s geological past becomes its most reliable performance indicator. By connecting geological principles to natural stone’s practical benefits, you make choices grounded in science rather than speculation. This knowledge empowers better specification, installation, and long-term satisfaction with natural stone investments in any application.